Part 1 of 7 — A Weekly Sunday Exclusive Series

An in-depth look at the most powerful drug lords in history, how they built their empires, and the lasting damage they left behind.

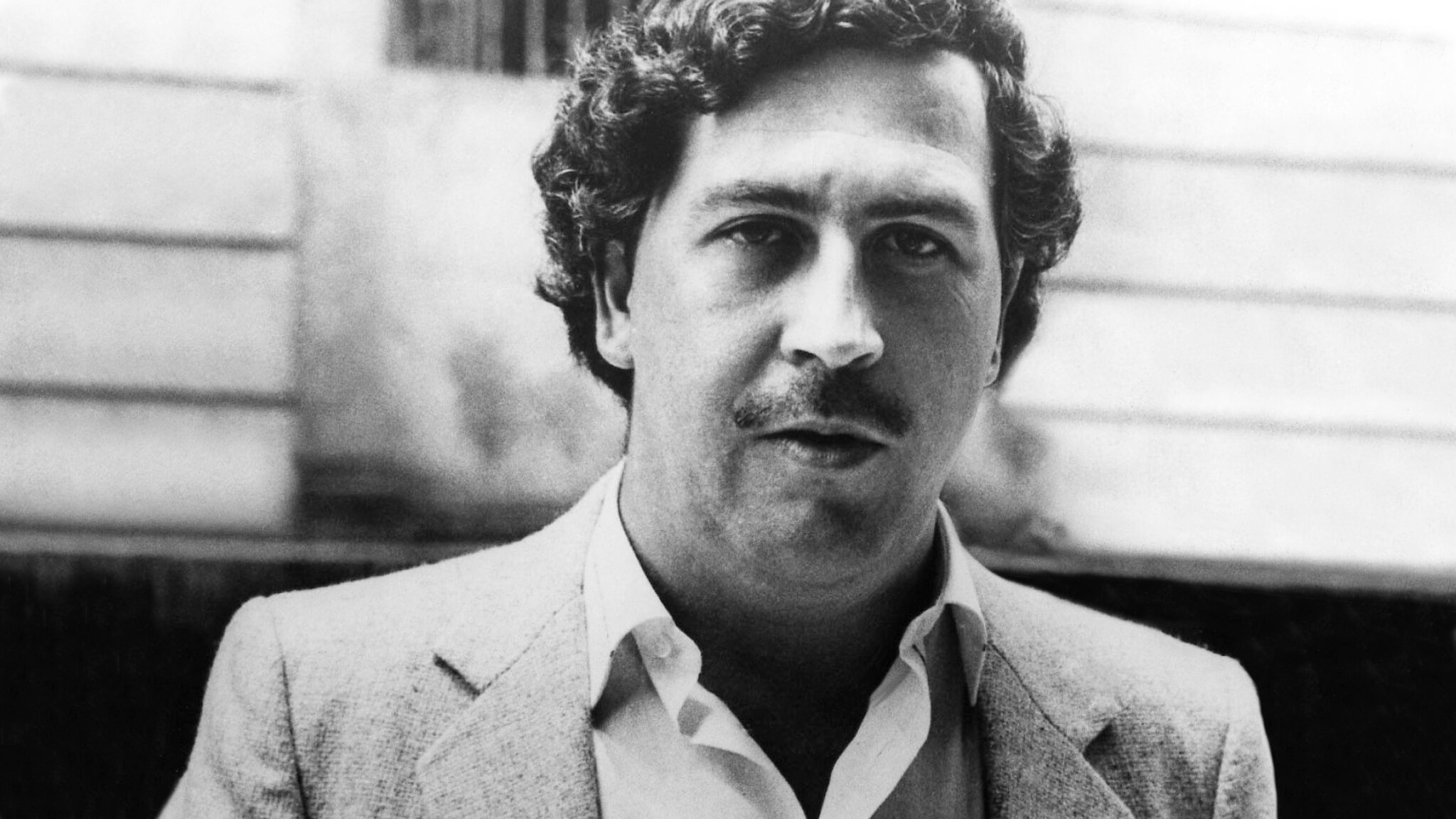

Few figures in modern history have been as widely discussed, or as deeply misunderstood as Pablo Escobar. As the leader of Colombia’s Medellín Cartel, Escobar became one of the most powerful criminals the world has ever known, operating at the center of a rapidly expanding global cocaine market during the late 20th century.

At his height in the 1980s, Escobar controlled a significant portion of the international cocaine trade, generating enormous wealth and influence. His story is inseparable from Colombia’s broader struggles with inequality, political instability, and the explosive global demand for narcotics during that era.

Born in 1949 in Rionegro, Colombia, Escobar grew up in modest circumstances. Like many young men in a country facing limited economic opportunity, he became involved in illegal activities early in life. What set Escobar apart was not just ambition, but an unusual ability to organize people, manage logistics, and identify emerging opportunities.

As cocaine demand surged in the United States and Europe during the 1970s, Escobar recognized the scale of what the drug trade could become. By the early 1980s, he had helped transform small smuggling operations into a structured organization with international reach.

Under Escobar’s leadership, the Medellín Cartel developed efficient supply chains linking coca producers, laboratories, transport networks, and distributors. The operation relied on aircraft, maritime routes, and extensive bribery to move product across borders.

Escobar was known for his hands-on management style and loyalty to those who worked for him. He paid well, protected allies, and demanded discipline. Qualities that helped him maintain control over a rapidly expanding enterprise.

Escobar’s wealth allowed him to live lavishly, but it also enabled him to fund infrastructure projects in poor communities. He supported housing developments, sports facilities, and local initiatives, particularly in Medellín’s marginalized neighborhoods.

For some residents, these actions earned him loyalty and admiration, complicating his public image. To others, he remained a criminal whose power reflected the absence of effective state support rather than genuine benevolence.

Fun fact: Escobar’s organization allegedly spent thousands of dollars every month just on rubber bands to hold together stacks of cash. There was so much money that losses from rot and rodents were considered routine.

As Escobar’s influence grew, so did tensions with the Colombian government and international authorities. His opposition to extradition to the United States became a defining issue, pushing him into direct confrontation with the state.

The resulting conflict marked one of the most turbulent periods in Colombia’s history. Violence escalated, and the country became a focal point of the global war on drugs.

In 1991, Escobar agreed to surrender under unusual conditions, serving time in a custom-built facility known as La Catedral. When those arrangements collapsed, he went on the run, prompting a large-scale manhunt.

On December 2, 1993, Pablo Escobar was killed in Medellín during an operation by Colombian security forces. His death marked the end of an era but not the end of the drug trade. Other organizations quickly filled the vacuum, illustrating how deeply entrenched the global narcotics economy had become.

Pablo Escobar’s legacy is complex. He was neither a simple villain nor a misunderstood hero, but a product of specific economic, political, and social conditions. His life highlights how quickly power can accumulate in environments marked by inequality and weak institutions.

Decades later, Escobar remains a symbol of ambition, excess, and the far-reaching consequences of illicit global markets.

Did you know?

Pablo Escobar once kept a private zoo at his estate, Hacienda Nápoles, which included four hippopotamuses illegally imported from Africa. After his death, the animals were left behind and eventually escaped into nearby rivers. With no natural predators, they multiplied rapidly and today form the only wild population of hippos outside Africa. A lasting and unexpected consequence of Escobar’s excess. They are now known as Cocaine Hippos.

Next week: Part 2 of 7 — Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán

Reports are sourced from official documents, law-enforcement updates, and credible investigations.

Discover additional reports, market trends, crime analysis and Harm Reduction articles on DarkDotWeb to stay informed about the latest dark web operations.